For Teachers: Lessons

Rethinking the rise of the West: Global Commodities

Konstantin Georgidis, Canterbury School, Ft. Myers, Florida

CLASS ACTIVITIES: Comparing and Contrasing Points of View

A. Silver Connects the World: China

- Have students watch the video "Early Global Commodities" on the web site.

- Students should be asked then to review the first segment of the video entitled, "Silver Connects the World: China."

VIDEO SEGMENT # 1 : Silver Connects the World: China

"This segment explores China's contribution to the creation of a global silver market during the sixteenth century. By the fifteenth century, China had been producing prized commodities like silk, jade, tea, and porcelain for hundreds of years. The Chinese exchanged these items within a thriving system of domestic trade, long-distance land-based trade, and tributary trade with nearby states. Because of these well-established trade networks, there were few trade items the Chinese needed from other channels.That changed in the mid-fifteenth century, when the Ming government's century-old system of using paper currency finally collapsed. At that point, the government adopted silver as its preferred medium of exchange, and promised from then on to pay all salaries — and to collect all taxes — in silver. The result was an explosion in demand for silver throughout China. Without adequate silver resources of its own to satisfy such demand, however, China had to look beyond its own borders.

Initially, the Chinese imported most of their silver from Japan, whose mines produced nearly a third of the world's silver output in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. However, by the 1540s it was already clear that the Chinese demand would outstrip the Japanese supply. It was at nearly that moment that silver from the Peruvian mine at Potosí was making its way onto the market — a historical convergence that would set the first global trading network in motion."

Summary from Bridging World History web site Unit 15-- see web site.

- Using an outline map of the world, ask students to map the flow of silver trade in the 17th century.

Reference materials --

In addition to the video program the following sources:- Asia for Educators web site "China and Europe: 1500 – 1800" The Silver Trade Part 1:Flow of Silver Interactive in http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/chinawh/web/s5/s5_4.html

- Worlds Together Worlds Apart textbook by Robert Tignor et.al. Chapter 4, Map: Trade in Silver and Other Commodities 1650-1750

- Direct students to peruse the section "The Silver Trade Part I" in the Web module China and Europe 1500-2000 and Beyond What is Modern? (Asia for Educators website)

- Class discussion: ask students to draw on what they have learned from the sources above to discuss the following propositions:

- "In the second half of the 15th and the first half of the 16th century it was China and the far East and not Europe that was the engine of international trade."

- "The failure of the Ming emperors to manage China’s money supply resulted in the complete "silverization" of the Chinese economy with enormous repercussions not only for the Chinese economy itself but also for the modern world economy at large."

- Ask students to examine the following primary sources and explain their significance for international trade in the sixteenth century.

Jade BI Disc with Qilong (ca 960-1279)

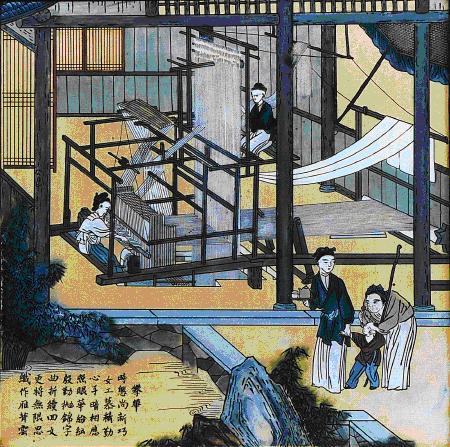

Chinese aristocrats weaving silk

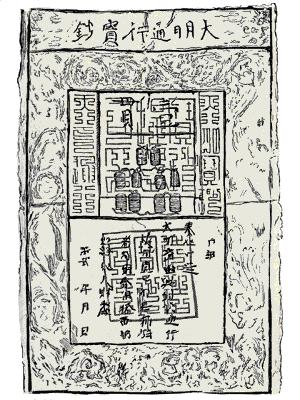

Chinese paper money Ming dynasty

Silver coin from Mexico Carlos IV minted 1798

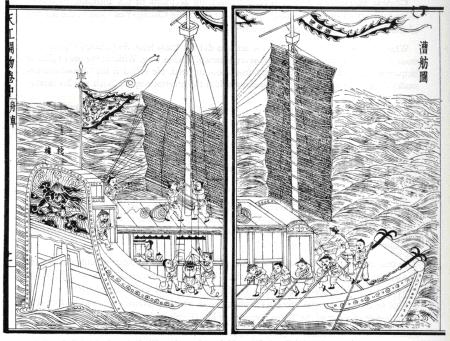

Chinese grain freighter 1639