The Song Confucian Revival

|

|

Old Trees, Level Distance, Northern Song dynasty (960-1127) “Guo Xi was the preeminent landscape painter of the late eleventh century. Although he continued the Li Cheng (919–967) idiom of ‘crab-claw’ trees and ‘devil-face’ rocks, Guo Xi’s innovative brushwork and use of ink are rich, almost extravagant, in contrast to the earlier master’s severe, spare style. ...” Learn more about this painting at the Metropolitan Museum website.

|

The Three Perfections

The life of the educated man involved more than study for the civil service examinations and service in office. Many took to refined pursuits such as collecting antiques or old books and practicing the arts — especially poetry writing, calligraphy, and painting (“the three perfections”). For many individuals these interests overshadowed any philosophical, political, or economic concerns; others found in them occasional outlets for creative activity and aesthetic pleasure.

In the Song period the engagement of the elite with the arts led to extraordinary achievement in calligraphy and painting, especially landscape painting. But even more people were involved as connoisseurs. A large share of the informal social life of upper-class men was centered on these refined pastimes, as they gathered to compose or criticize poetry, to view each other’s treasures, or to patronize young talents.

Su Shi (Su Dongpo, 1036-1101)

A good example of a scholar-official with strong interests in the arts is Su Shi (1036-1101). After making a splash in the examinations, Su Shi became something of a celebrity. Su was a superb and prolific writer of both prose and poetry. Because he took stands on many of the controversial political issues of his day, he got into political trouble several times and was repeatedly banished from the capital.

Best known as a poet, Su was also an esteemed painter and calligrapher and theorist of the arts. He wrote glowingly of paintings done by scholars, who could imbue their paintings with ideas, making them much better than paintings that merely conveyed outward appearance, the sorts of paintings that professional painters made.

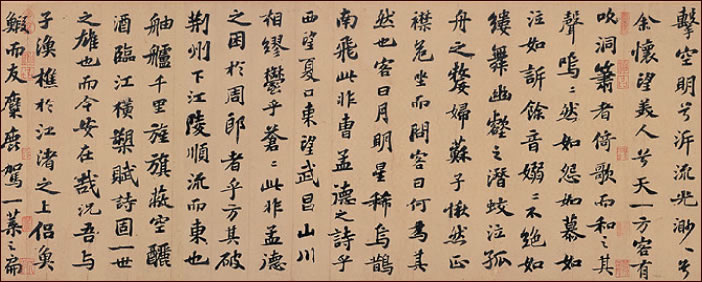

| Detail from Su Shi’s “Former Ode on the Red Cliff,” c. 1083; handscroll; ink on paper © National Palace Museum |

|

| Learn more about this painting at the National Palace Museum website. To access the work, wait for the Flash website to load, then select Scholar Art from the bottom menu. |

The following is a translation (by Pauline Chen) of the above Former Ode, also known as the “First Prose Poem of the Red Cliffs”:

In the autumn of 1082, on the 16th of the seventh month, Master Su and his guests sailed in a boat below the Red Cliffs. Clear wind blew gently, the water was calm. The boaters raised their wine and poured for each other, reciting “The Bright Moon” and singing “The Lovely One.”

After a while, the moon rose above the eastern mountain, and hovered between the Dipper and the Cowherd star. White mist lay across the water; the light from the water reached the sky. They went where their tiny boat took them, floating on a thousand leagues of haze, in the vastness as if resting on emptiness and riding the wind, not knowing where they would stop, floating as if they had left the earth and stood alone, having turned into birds and become immortal. And so they drank and their joy reached its height, and they sang beating on the side of the boat. The song went:

Cassia oars and orchid paddles

Beat the illusory moon,

Rowing against the flow of streaming light.

From a great distance my heart

Yearns for my beloved at one end of the sky.Among the guests there was one who played the flute, and he played along with their song. The sound of his flute mourned, as if grieving as if loving, as if weeping as if reproaching. Its sound echoed and lingered, not breaking as if a silken thread. It set to dancing the dragon submerged in a deep crevice, and brought to tears the widow in the lonely boat.

Master Su sobered himself, and straightening his collar sat upright. He asked the guest: “Why did you play like that?” The guest replied, “‘The moon is bright, the stars, sparse. The crows and magpies fly south,’ aren’t these the words from Cao Cao’s poem? Looking west towards Xiakou, East towards Wuchang, with the mountains and rivers entwining each other, densely green — isn’t this the place where Cao was beseiged by Zhou Yu? Cao had just broken Jingzhou, and was going to Jiangling, sailing west with the flow of the river. His boats prow to stern stretched for a thousand miles, and his flags and banners blocked the sky. Pouring wine, looking down on the river, chanting poems with a spear across his knees, he was indeed a hero of his times; but today, where is he? And how about you and I, fishermen and woodcutters on the islets in the river, taking the fish and shrimp and deer as our companions, and riding in a leaf of a boat, raising gourds as our goblets and drinking to each other? Entrusted like flies to heaven and earth, as tiny as one grain in a vast ocean. I grieve at my life’s shortness, and envy how the Great embrace the moon and live forever. I know that I cannot quickly achieve this, and I entrusted these sounds to the sad wind.”

Master Su said, “Do you know the water and moon? The one flows on, and yet never goes anywhere, and the other waxes and wanes, yet never diminishes or grows. If you look at them from the point of Change, then heaven and earth never stay the same for even the blink of an eye. If you look from the point of what is unchanging, then all things, and I, are inexhaustible, so what is there to envy? Between heaven and earth, each thing has its master, and if it were not mine, even if only a hair, I would not take it. Only the clear wind on the river, and the bright moon between the mountains: the ear receives one and creates sound, the eye meets the other and makes color; you can take these without prohibition, and use them without exhausting them. This is the infinite treasure of the Creator, and what you and I can share and rejoice in.”

The guest was pleased and smiled, they washed the cups and refilled them. All the dishes were finished, and the cups and plates were scattered all over. Pillowing on each other in the middle of the boat, they didn’t see that the sky was already brightening in the east.