China and Europe: 1500-1800

China: An "Early Modern" Society, Part 2

Everybody Counts

Productive Policies [VIDEO]

TRANSCRIPT: In trying to realize their economic goals, which were basically the goals of enabling as many people as possible to live with reasonably secure, modest subsistence, a little bit extra above that, and the ability to pay their taxes without excruciating pain, the Qing followed a series of policies designed to promote economic growth within the limits of a premodern world, which was the only world they knew.

And they did a number of things that were quite successful. They promoted migration to use land that was being underused. They promoted the growth of handicrafts, especially textiles, both to give people things to wear and to give rural families a second source of income, particularly as farms tended to get smaller. As the population grew you couldn't employ the whole family on the farm.

And so what tends to happen in the richer and more crowded parts of China is that women get out of agriculture and start to work more or less full time making cloth and selling it on the market. They (the Qing government) promote that in all sorts of ways. They try to promote relatively easy exchange of grain. So that if one local area has a crop failure, there's a way to get grain in. And they do that both by encouraging the market and also by providing for the creation of emergency granaries. So that in areas where the market fails for one reason or another, they know what to do about it.

And again they're quite sophisticated about that. If you look at where they locate their granaries, they don't locate their granaries right along the Yangzi River. Because they understand that the Yangzi River is an 800-mile, well, more than 800-mile, but within the core of China, it's an 800-mile-long highway that grain can move back and forth along there. And that places there are likely to be able to solve any local harvest problem by market means.

If there's a bad harvest in place X that's right along the Yangzi, there's no need to store grain there. You just give them silver and with silver they can purchase grain from up river. The places where you need to physically store grain are the places that are not on a river. Because shipping stuff over land is tremendously expensive. If you give some landlocked place a pile of silver, you can't eat it. And you can't ship grain in all that easily.

And the Qing understand that, and it's precisely in the landlocked places that they build government granaries to make sure that there will be grain. And they have a whole series of policies like that, which are designed to encourage this kind of economy.

The Qing dynasty built granaries in an attempt to ensure subsistence, and thinking very systematically about the ecological diversity of China, said, "In this place, which is close to river transport, we're not going to need to build granaries. Here the market will work, and we can just give them silver to buy grain from up-river in an emergency. In that place we had better have the grain because it's landlocked."

A European view of officials distributing grain in a famine-struck area.

Columbia University Libraries

When both the Ming and Qing dynasties faced threats in the northwest and had to deploy large armies in this relatively arid region, they were not going to be able to feed their forces from the local food supply, so they came up with some very clever tricks. They told merchants that if they were willing to move grain cheaply up to the northwest—essentially to move it at a loss—the government would reward them with the right to participate in the government salt monopoly, which was a place where one could make big money. So once again this was a regime that was drawing on a very complicated repertoire of techniques for managing a preindustrial economy. None of these techniques triggered an industrial revolution, but they did produce a remarkably sophisticated and advanced commercial economy that was able to support an enormous population without pushing it into poverty. And in the eighteenth century that was about as good as anybody was doing anywhere.

Moving Food and Populations [VIDEO]

TRANSCRIPT: The Chinese state is fundamentally engaged with its countryside from an early date. The Chinese state, also from a very early date, is thinking deeply about the problems of moving food around for its own purposes. One of the reasons for this is simply ecological. For most of the last, couple thousand years, China's capital has tended to be in the north. In part because, for reasons of defense against the nomadic peoples of Central Asia, it often made a lot of sense to kind of concentrate your regime up there—to have your troops and so forth where they faced the threat.

But there's a problem, in premodern conditions, with having a big capital (city), then, for obvious reasons. Whatever China's capital city is, (it) has almost always been one of the largest cities in the world. Having a capital and having a huge army in north China (is a problem), because north China is the least fertile part of the country. And under premodern conditions, where it's very hard to ship grain—grain being bulky—any very large distance overland ... it starts getting incredibly expensive.

Feeding a large capital city and an army is a huge problem. Especially in conditions in the north where, because there's much less rainfall, agricultural yields are not particularly bountiful. Most of the farmers in the surrounding countryside don't have large surpluses above their own needs. If you try and feed the capital city and the army strictly by taxing grain away from them, you're very, very quickly going to exhaust them. And you're going to have major uprisings.

This is not a uniquely Chinese problem. It's a problem all over the place. Capital cities in Europe like Madrid and Potsdam, Berlin, both of which are in not particularly fertile areas. And even Paris, which is in a sort of moderately fertile area, cause constant problems for their surrounding countryside, because the capital city is this gigantic stomach that's sucking the grain in out of the countryside.

Well, the way the Chinese solve the problem is essentially a byproduct of the Chinese migration into what is today South China. Once a lot of the population moves to the south, where the growing season is longer, rainfall is better, and it's just in general a much friendlier ecology, it's the south rather than the north that produces huge quantities of grain surplus.

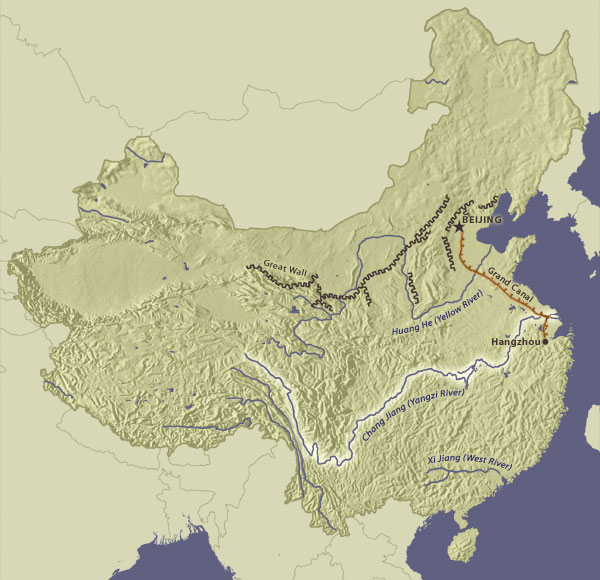

So then the question becomes, you've got a capital and an army way up in the north; you've got this surplus food being produced in the south. What are you going to do about it? Well one of the things the Chinese do from a very early date is dig the world's largest canal. What we call the Grand Canal, which is begun in the sixth century (and) gradually extended over time. At its full extent it's over 1000 miles long. (It) develops originally for purposes largely of feeding the capital and the army with southern grain.

But of course once it is in place, it's also a commercial artery area that people can use for other things. So there is this Chinese tradition going way, way back of thinking about, how do I move grain? How do I do it in the way that's least burdensome to the people, so that I don't get uprisings? So that the burden of supplying extra grain is falling on the southerners, who are richer, rather than the northerners who are poorer but happen to be nearby.

These are problems that they had been thinking about for a very long time. And they devised really remarkably clever means of dealing with both technological means like the Grand Canal, but also social and institutional means.

The Qing did this much more systematically than anyone before them in China. But in some sense they were also heirs to a very long tradition of thinking about grain supply. It was a fundamental responsibility of the government, which was quite unusual. If you think about what European governments were doing in the early modern period, about grain supply, it was fundamentally different.

When European governments intervened in the grain supply, it was almost always either to ensure that the army got fed or that the major cities got fed. Those were the two groups of people the government was most worried about. And it went back to a long tradition in the West of cities having special political status.

The Qing Government and Women's Handicrafts[VIDEO]

TRANSCRIPT: The Qing are very conscious that rural households will be better off if they have some source of income besides farming. They also believe very strongly that a woman who has an income-producing skill is both a better woman morally, that she sets an example of diligence et cetera that her children learn from. And so, unlike in Europe where it's often thought that the ideal mother is the one who doesn't work for the market—that the market somehow sullies her—in China, on the contrary, the woman who can produce income and who gives her children an example of diligence by doing so, is thought to improve her mothering. And also in a very practical way, they know that some percentage of women are going to wind up (being) widows. And that a widow who knows how to spin and weave is a lot more likely to survive and to raise her kids successfully and so on and so forth, than a woman who can't do those things. And so one of the things that the Qing do very aggressively is to promote rural handicrafts, especially textiles. And their efforts are modest by the standards of a twentieth-century government. They don't have the kind of capabilities that modern states do. But by the standards of a premodern government, they're actually quite astonishing. In areas that don't grow cotton, they distribute seeds and print up thousands and thousands of copies of very simple pamphlets about how to grow the stuff. So that there will be cotton for the women to spin and to weave. They give demonstrations of how to use a loom because you handle cotton differently from the way you handle hemp or ramie or the other things that people were making clothing out of before. And they realized that people need to be instructed. This is a mass education and employment project on a pretty impressive scale. And though we tend to forget it, because of course the long run story is that rural handicraft production eventually is going to be wiped out by mechanized industry, nobody knew that in 1600 or 1700. And given what they knew, this is a remarkably successful example of intervention (in the rural economy).

However, the Chinese notion was that, in a sense, everybody counted and that rural subsistence was something the government should be fundamentally concerned with. The European state in many ways, until modern times, ceded the countryside to the aristocracy, and/or the church, effectively saying, "It's not our problem."

Yangzi River and the Grand Canal